This website showcases my book-in-progress on the adventures of a French woman in Persia in the early years of the 18th century. What follows below is a brief description of her story, told mainly from her point of view. As you will see when you explore the site (currenly under construction), all of this is open to interpretation as each of the interested parties struggled to convey their version of events in the contemporary letters, legal documents and manuscript memoirs which survive from the time.

In December 1702, Marie Petit was running a successful (if technically illegal) gambling house or tripot on the rue Mazarine in Paris. As chance would have it, one of her neighbours and clients was Jean-Baptiste Fabre, a scion of a wealthy Marseille manufacturing family who was soon to be appointed France’s first ever extraordinary ambassador to Persia. The mandate of the mission was to negotiate a trade treaty on favourable terms for French merchants, not least of which the Fabre family.

When Fabre finally managed to secure the coveted appointment as ambassador to Persia, he soon realised he had a problem on his hands. King Louis XIV had been generous with his presents for Shah Soltan Hussayn, but, in keeping with the usual practice of the time, his ambassador could only expect to be remunerated on completion of his mission. Fabre was unable to come up with the ready cash to finance the journey, and turned to Petit, who agreed to lend him 8000 livres for initial expenses.

The loan is recorded in a promissory note, although its precise terms and conditions are murky. When Fabre set out for Toulon in 1705, Petit felt compelled to join him in order to protect her investment. Besides, Fabre had indicated that she might find an interesting business opportunity importing Persian goods (mainly textiles) into France.

Petit assumed male dress and embarked with Fabre on the royal vessel Le Trident captained by Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Turgis.

By June 1706, Fabre and Petit had reached Erivan, the capital of a Persian province then on the north-western frontier of the empire. They were received hospitably enough by the ruling Khan, but on the 16th of August, Fabre died suddenly of apparent poisoning following a hunting party.

To protect her claim on Fabre’s estate, Petit decided to take up the reins of the mission, styling herself ambassador of the French princesses. She then proceeded towards the Shah’s court.

Hot on her heels was a replacement ambassador, Pierre Victor Michel, second secretary to the resident ambassador at Constantinople, Charles Ferriol. Ferriol, acting in concert with the minister of the navy Jérôme de Pontchartrain, was desperate to get Petit out of Persia before she could damage the French national honour with her scandalous behaviour. She was, after all, in their view, nothing but a whore who had travelled with Fabre as his concubine for mercenary reasons (another interpretation of the promissory note was that it was the price of Petit’s company on the journey, rather than a loan from Petit to Fabre).

Michel ultimately succeeded in getting Petit to return to France, but not before she extracted from him another note, replacing the original note from Fabre, promising to reimburse her 12000 livres out of Michel’s private fortune.

On Petit’s return to Marseille in 1709, Michel had laid a trap for her. By royal order, the city magistrates were to take her directly from quarantine to the women’s prison, the notorious ‘Hôpital du Refuge.’ Michel hoped thus to silence Petit, and prevent her claiming the 12000 livres.

However, Petit would not be silenced. She began a letter-writing campaign to Pontchartrain in Versailles, demanding justice and a regular trial. The trial was granted and stretched on into 1713, and it did not go in Petit’s favour, although she did secure her freedom. She was forced to sell off the goods she had brought back from Persia.

The matter did not rest there, though. Michel, who had managed to parlay his success in negotiating the trade treaty with the Shah of Persia into a post as French consul at Tunis, did not live to enjoy his promotion for long. After his death in 1718, Petit relaunched her suit for the 12000 livres against Michel’s heir, his sister Claire Michel.

Petit’s story speaks to me of the position of socially marginal women in early 18th century France. Her competition with Michel, a man from a non-noble, artisan family, provides us with an intriguing comparison along gender lines. What were the avenues for social and financial advancement open to each? How did they seek to manipulate the existing bureaucratic and legal systems in their favour? How and why did they succeed or fail? What was the role of private family interests – such as those of the Fabre family – in determining foreign policy? Did Petit suffer the treatment she did because she offended moral codes or because she got in the way of these family interests?

In December 1702, Marie Petit was running a successful (if technically illegal) gambling house or tripot on the rue Mazarine in Paris. As chance would have it, one of her neighbours and clients was Jean-Baptiste Fabre, a scion of a wealthy Marseille manufacturing family who was soon to be appointed France’s first ever extraordinary ambassador to Persia. The mandate of the mission was to negotiate a trade treaty on favourable terms for French merchants, not least of which the Fabre family.

When Fabre finally managed to secure the coveted appointment as ambassador to Persia, he soon realised he had a problem on his hands. King Louis XIV had been generous with his presents for Shah Soltan Hussayn, but, in keeping with the usual practice of the time, his ambassador could only expect to be remunerated on completion of his mission. Fabre was unable to come up with the ready cash to finance the journey, and turned to Petit, who agreed to lend him 8000 livres for initial expenses.

The loan is recorded in a promissory note, although its precise terms and conditions are murky. When Fabre set out for Toulon in 1705, Petit felt compelled to join him in order to protect her investment. Besides, Fabre had indicated that she might find an interesting business opportunity importing Persian goods (mainly textiles) into France.

Petit assumed male dress and embarked with Fabre on the royal vessel Le Trident captained by Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Turgis.

By June 1706, Fabre and Petit had reached Erivan, the capital of a Persian province then on the north-western frontier of the empire. They were received hospitably enough by the ruling Khan, but on the 16th of August, Fabre died suddenly of apparent poisoning following a hunting party.

To protect her claim on Fabre’s estate, Petit decided to take up the reins of the mission, styling herself ambassador of the French princesses. She then proceeded towards the Shah’s court.

Hot on her heels was a replacement ambassador, Pierre Victor Michel, second secretary to the resident ambassador at Constantinople, Charles Ferriol. Ferriol, acting in concert with the minister of the navy Jérôme de Pontchartrain, was desperate to get Petit out of Persia before she could damage the French national honour with her scandalous behaviour. She was, after all, in their view, nothing but a whore who had travelled with Fabre as his concubine for mercenary reasons (another interpretation of the promissory note was that it was the price of Petit’s company on the journey, rather than a loan from Petit to Fabre).

Michel ultimately succeeded in getting Petit to return to France, but not before she extracted from him another note, replacing the original note from Fabre, promising to reimburse her 12000 livres out of Michel’s private fortune.

On Petit’s return to Marseille in 1709, Michel had laid a trap for her. By royal order, the city magistrates were to take her directly from quarantine to the women’s prison, the notorious ‘Hôpital du Refuge.’ Michel hoped thus to silence Petit, and prevent her claiming the 12000 livres.

However, Petit would not be silenced. She began a letter-writing campaign to Pontchartrain in Versailles, demanding justice and a regular trial. The trial was granted and stretched on into 1713, and it did not go in Petit’s favour, although she did secure her freedom. She was forced to sell off the goods she had brought back from Persia.

The matter did not rest there, though. Michel, who had managed to parlay his success in negotiating the trade treaty with the Shah of Persia into a post as French consul at Tunis, did not live to enjoy his promotion for long. After his death in 1718, Petit relaunched her suit for the 12000 livres against Michel’s heir, his sister Claire Michel.

Petit’s story speaks to me of the position of socially marginal women in early 18th century France. Her competition with Michel, a man from a non-noble, artisan family, provides us with an intriguing comparison along gender lines. What were the avenues for social and financial advancement open to each? How did they seek to manipulate the existing bureaucratic and legal systems in their favour? How and why did they succeed or fail? What was the role of private family interests – such as those of the Fabre family – in determining foreign policy? Did Petit suffer the treatment she did because she offended moral codes or because she got in the way of these family interests?

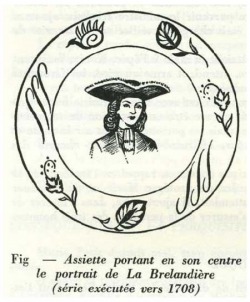

Mystery Ceramic

Image from Yvonne Gres, La belle brelandiere (Paris, 1973). I am seeking any information regarding this plate, purportedly made in Tabriz around 1708. If you have any leads, please contact me [email protected]