The author in Imam Square

I am a lecturer in French literature at University College London. I became interested in Franco-Persian relations when I travelled to Iran in June 2003 to accompany my friend Tehnyat Majeed who was doing some fieldwork for her doctorate on Square Kufic script.

Tehnyat sketching in the Pir-i Bakran shrine

From our base in Isfahan, we went by taxi to the Pir-i Bakran shrine in the village of Linjan, some 30 km outside of the city. After a day’s hot and dusty work sketching and measuring the fragments of calligraphy in the shrine’s stone and stucco work, we rewarded ourselves with some architectural tourism in Isfahan, as well as eating delicious vanilla and rose-water ice-cream on Naqsh-e-Jahan (Imam) Square and shopping for a carpet and saffron in the Grand Bazaar.

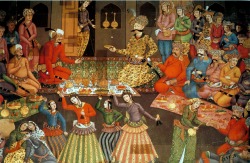

Shah Abbas I receiving Vali Muhammad Khan

When we toured the Chihil Sutun palace, I was intrigued by the wall paintings, some of which are in a Europeanizing style with shading and perspectival rendering. Some of the paintings also depict European visitors. The palace was built at the behest of Shah Abbas II in around 1647, and the paintings may date from the late 17th century (with some later overpainting).

Since my research specialism is the early modern period (see link to my previous book), I began to be curious about encounters between European visitors and the Safavid court. When I returned to London, I read a number of books on the history of Iran in this period looking for connections with France, including Roger Savory’s Iran under the Safavids (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980) (see preview on Google Books).

I first encountered Marie Petit in Savory’s chapter ‘Relations with the West during the Safavid Period.’ He describes the Fabre mission and Petit’s role in it as ‘pure farce interspersed with tragedy’ (p. 121).

A particular incident which took place after Fabre’s death in Erivan especially fascinated me. One day, when the French were seated at table, Petit threw an orange at a servant who had initially neglected to offer her the fruit basket and instead served Fabre’s young nephew. In retaliation for being hit by the orange, the servant then attacked and tried to kill Petit. This escalated into a full-scale riot and finally a gunfight between the French and Persian soldiers which caused several deaths.

How could a seemingly trivial slight get so out of hand? It sounded like a scene from an 18th century comic novel like Moll Flanders or Tristram Shandy, or even a movie (for some reason I have Pirates of the Caribbean in mind, but perhaps I’ll think of a better comparison at some point).

I liked Petit’s bold, somewhat melodramatic gesture of lobbing the orange at the negligent servant. The quick descent into violence suggested to me a level of tension in diplomatic relations between the French visitors and their Persian hosts that resonated with the current climate between Iran and the west.

In short, I was hooked. The more I read about Petit in both the archival sources and later accounts of her (both fictional and factual treatments), the more I was drawn to try to tell her story in a way in which no one else has really tried to do.

Most of the purportedly factual accounts, all written by men, tend to treat Petit as a fly in the ointment - an interference in the official business of diplomacy. None of them really consider her point of view. Although they may show a grudging admiration for her powers of seduction, they don’t ask too many questions. Why did she undertake the journey? What was she hoping to gain? Why did she attract such hostility from the French political establishment?

Maulde La Clavrière (1896) suggests she did it out of a spirit of adventure which I think shows a sympathetic measure of feminism but I don’t think fully explains Petit’s behaviour.

The only woman to write about Petit, and the most recent (Grès 1973), imagines her journey as frivolous shopping trip over the course of which she made a number of exotic romantic conquests. Having read the inventory of belongings with which Petit returned from Persia and which she was later forced to sell at auction (the sale took several days, there was so much stuff), I acknowledge that there may be a degree of truth to Grès’s presentation but I certainly don't think that was all there was to it.

So there you have it. The genesis of the Marie Petit Project, for want of a better title.

Since my research specialism is the early modern period (see link to my previous book), I began to be curious about encounters between European visitors and the Safavid court. When I returned to London, I read a number of books on the history of Iran in this period looking for connections with France, including Roger Savory’s Iran under the Safavids (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980) (see preview on Google Books).

I first encountered Marie Petit in Savory’s chapter ‘Relations with the West during the Safavid Period.’ He describes the Fabre mission and Petit’s role in it as ‘pure farce interspersed with tragedy’ (p. 121).

A particular incident which took place after Fabre’s death in Erivan especially fascinated me. One day, when the French were seated at table, Petit threw an orange at a servant who had initially neglected to offer her the fruit basket and instead served Fabre’s young nephew. In retaliation for being hit by the orange, the servant then attacked and tried to kill Petit. This escalated into a full-scale riot and finally a gunfight between the French and Persian soldiers which caused several deaths.

How could a seemingly trivial slight get so out of hand? It sounded like a scene from an 18th century comic novel like Moll Flanders or Tristram Shandy, or even a movie (for some reason I have Pirates of the Caribbean in mind, but perhaps I’ll think of a better comparison at some point).

I liked Petit’s bold, somewhat melodramatic gesture of lobbing the orange at the negligent servant. The quick descent into violence suggested to me a level of tension in diplomatic relations between the French visitors and their Persian hosts that resonated with the current climate between Iran and the west.

In short, I was hooked. The more I read about Petit in both the archival sources and later accounts of her (both fictional and factual treatments), the more I was drawn to try to tell her story in a way in which no one else has really tried to do.

Most of the purportedly factual accounts, all written by men, tend to treat Petit as a fly in the ointment - an interference in the official business of diplomacy. None of them really consider her point of view. Although they may show a grudging admiration for her powers of seduction, they don’t ask too many questions. Why did she undertake the journey? What was she hoping to gain? Why did she attract such hostility from the French political establishment?

Maulde La Clavrière (1896) suggests she did it out of a spirit of adventure which I think shows a sympathetic measure of feminism but I don’t think fully explains Petit’s behaviour.

The only woman to write about Petit, and the most recent (Grès 1973), imagines her journey as frivolous shopping trip over the course of which she made a number of exotic romantic conquests. Having read the inventory of belongings with which Petit returned from Persia and which she was later forced to sell at auction (the sale took several days, there was so much stuff), I acknowledge that there may be a degree of truth to Grès’s presentation but I certainly don't think that was all there was to it.

So there you have it. The genesis of the Marie Petit Project, for want of a better title.